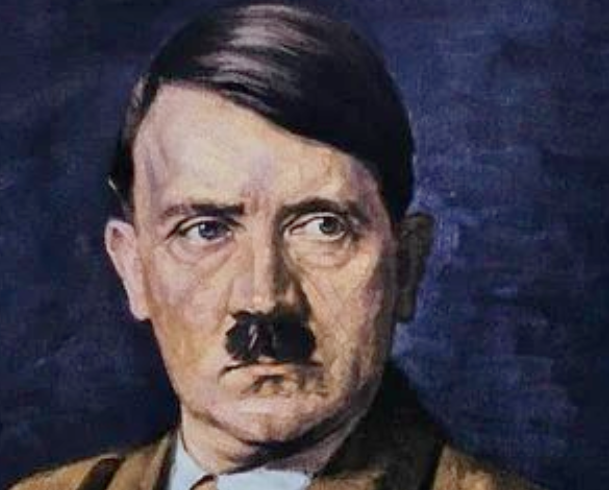

The complex topic of Hitler religion reveals he was not a traditional Christian, atheist, or pagan. He rejected his Catholic upbringing for a twisted pseudo-religion, a syncretic belief system blending social Darwinism, a pantheistic worship of nature, and a messianic deification of the Aryan race. This political faith provided the ideological justification for the horrors of the Third Reich.

| Religion: | Rejected his Roman Catholic upbringing; developed a syncretic pseudo-religion based on social Darwinism, pantheism, and a racial ideology that deified the “Aryan race.” |

| Profession: | Politician, Dictator of Nazi Germany |

| Date of birth: | April 20, 1889 |

| Zodiac sign: | Aries |

| Nationality: | Austrian-born German |

Hello, I’m Frenklen, a historian with over 15 years of experience specializing in the ideologies of 20th-century totalitarian regimes. For decades, the question of Hitler’s religion has been a source of intense debate and deliberate misinformation.

Was he a devout Christian, a staunch atheist, a dabbler in the occult? The truth, as is often the case with such complex figures, is far more nuanced and disturbing. Many try to pigeonhole him to fit a particular narrative, but this oversimplification misses the very essence of what drove him. As historian Richard Weikart meticulously documents in his work, Hitler forged his own dark faith—a political religion that was instrumental in shaping the Third Reich.

In this article, we will move beyond the simplistic labels. We’ll dissect the twisted tapestry of his beliefs, drawing from his own words in speeches and writings like Mein Kampf, and the private accounts of his closest associates. Prepare to explore the chilling synthesis of pseudo-science, racial mysticism, and political messianism that constituted the true religion of Adolf Hitler. Understanding this is not just an academic exercise; it’s a vital lesson on how ideology can morph into a destructive belief system with catastrophic consequences.

Hitler and Early life and religion

To comprehend the complex and destructive nature of Hitler’s religion, one must first examine his origins and early relationship with traditional faith. Adolf Hitler was born in Braunau am Inn, Austria, into a Catholic family, and this upbringing shaped his initial exposure to religious concepts. He was baptized as a Roman Catholic, and his mother, Klara Hitler, was a devout and practicing Catholic.

Her faith was a significant presence in the household, and she ensured that her children, including Adolf, received a Catholic upbringing. For a time, the young Hitler seemed to embrace it. He attended a monastery school and was reportedly a member of the choir, even entertaining the idea of one day becoming a priest. He was confirmed in the Catholic Church in May 1904 in the cathedral at Linz. These early experiences provided him with a deep familiarity with Christian liturgy, symbolism, and rhetoric, which he would later skillfully manipulate for political gain.

However, this youthful engagement with Catholicism did not last. Several factors contributed to his eventual and total rejection of Christian doctrine. His father, Alois Hitler, was a stark contrast to his devout mother. Alois was nominally Catholic but was deeply anticlerical and a freethinker, often expressing skepticism and disdain for the Church’s authority. This paternal influence likely planted the first seeds of doubt in Hitler’s mind. As he grew into a young man and moved to Vienna, his alienation from the Church intensified.

He was exposed to a volatile mix of pan-German nationalism, the racial theories of figures like Lanz von Liebenfels, and the pervasive antisemitism of the city’s political culture. These ideologies offered a new, competing worldview that was fundamentally incompatible with Christian teachings of universal love and compassion. He began to see Christianity, with its Jewish origins and its emphasis on protecting the weak and meek, as a “religion for slaves” that undermined the “master race” he was beginning to idolize. As the provided context notes, it is clear that “Hitler had turned his back on Catholic teaching.” This rejection was not a simple drift into atheism; it was a conscious replacement of one faith with another, far more sinister one—a political religion centered on race and struggle.

Hitler’s views on faith and spirituality

Adolf Hitler’s mature views on faith and spirituality were a complex and lethal amalgam of ideas that formed a cohesive, albeit horrifying, worldview. It cannot be accurately described by conventional religious labels. Instead, it was a pseudo-religion, a term that aptly captures its imitation of religious structure and fervor while being rooted in a secular, materialist ideology. The core tenets of Hitler’s religion were a blend of social Darwinism, a form of pantheistic nature worship, and a messianic belief in his own role as a savior of the German people.

At the heart of his belief system was a crude and brutal interpretation of Social Darwinism. Hitler believed that all of history, and indeed all of life, was an eternal and merciless struggle for existence between races. He saw this not as a mere sociological theory but as the fundamental, unchangeable law of nature, ordained by a higher power he often referred to as “Providence” or “the Almighty.” In his mind, the Aryan race was nature’s greatest creation, and it was its destiny to dominate or eliminate weaker races, particularly the Jews, whom he viewed as a parasitic counter-race.

This “pseudo-scientific” foundation, as the context highlights, allowed him to frame genocide not as a crime, but as a biological necessity—a painful but essential act of “racial hygiene” to restore the health of the German people. This belief system provided a moral justification for his most heinous acts; he was simply enforcing the “laws of nature.”

This belief in natural law was tied to a form of pantheism. Hitler did not believe in a personal, transcendent God who intervened in human affairs and offered salvation. Instead, his “Providence” was an impersonal, immanent force that expressed itself through the iron laws of nature: struggle, survival of the fittest, and racial purity.

He saw divinity in nature itself—in the strength of the wolf, the purity of the mountain stream, and, above all, in the “pure blood” of the Aryan race. This is why Nazi ideology placed such a strong emphasis on “Blood and Soil” (Blut und Boden). His spirituality was earthly and materialist. He once remarked that one could not grasp the National Socialist worldview unless one had “a sense of the great creative power of nature.”

Finally, this worldview was fused into a political religion with himself at its center. The Nazi movement adopted all the trappings of a church. It had a messianic leader (Hitler), a sacred text (Mein Kampf), saints and martyrs (like Horst Wessel), grand cathedrals of light at mass rallies, and ritualistic ceremonies that fostered a sense of collective ecstasy and total devotion.

Hitler privately expressed deep contempt for Christianity, viewing it as a weak, effeminate, and Jewish-born faith that preached a dangerous message of compassion. His long-term goal, as revealed in his private conversations, was the eventual eradication of Christianity from the Reich and its replacement with his own faith based on race, struggle, and loyalty to him as the Führer. This twisted belief system was the engine of the Third Reich, transforming politics into a holy war and providing the rationale for “the deaths of millions of innocent people through genocide and war.”

Hitler’s Parents’ Religion

The religious environment of Hitler’s childhood home was one of stark contrast, a dichotomy that undoubtedly influenced his later development and his ultimate formulation of the twisted ideology known as Hitler’s religion. His parents, Alois and Klara, held profoundly different views on faith, creating a household where piety and skepticism coexisted.

His mother, Klara Pölzl, was a quiet, unassuming woman and a devout Roman Catholic. Her faith was genuine and deeply felt, providing her with solace through a life marked by personal tragedy, including the deaths of several of her children in infancy. She ensured that Adolf and his siblings were raised within the Church, overseeing their baptism, attendance at Mass, and religious education. It was through her influence that Hitler was enrolled in a Benedictine monastery school in Lambach, where he sang in the choir and served as an altar boy. Klara’s gentle piety represented the traditional, institutional faith that Hitler would later come to despise, yet his affection for his mother was profound. After her death from breast cancer in 1907, a Jewish doctor who treated her, Eduard Bloch, noted that he had “never seen anyone so prostrate with grief as Adolf Hitler.” This personal tragedy, however, did not lead him back to his mother’s faith; instead, it may have hardened his view of a world governed by cruel, impersonal forces rather than a loving, personal God.

In direct opposition to Klara’s devotion stood his father, Alois Hitler. A mid-level customs official, Alois was a classic example of the late 19th-century anticlerical liberal. While he was nominally Catholic and had married Klara in the Church, he was a freethinker who was openly contemptuous of the clergy and the Church’s influence in society. He viewed the Church as a backward, superstitious institution that stood in the way of progress and rational thought. His dinner-table conversations often included tirades against priests and the papacy.

This constant exposure to his father’s skepticism provided the young Hitler with an alternative perspective to his mother’s piety. It gave him the intellectual tools and the permission, in a sense, to question and ultimately reject the authority of the Catholic Church. Alois’s worldview, which valued state authority and German nationalism over religious doctrine, laid a foundational stone for Hitler’s later belief that the Church was a rival power center that must be subordinated to the will of the nation and its leader. The clash between his mother’s heartfelt faith and his father’s cynical disdain created a vacuum that Hitler would eventually fill with his own brutal pseudo-religion.

Hitler’s Life Partner’s Religion

Eva Braun, the woman who was Adolf Hitler’s long-term companion and, for less than 40 hours, his wife, existed in a world almost entirely defined by him. Her own religious beliefs, therefore, were largely overshadowed and are not a matter of deep historical record, but they provide a small window into the private life of the Führer and the nature of his inner circle. Eva Braun was raised in a middle-class, conventional German family in Munich. Her parents were practicing Catholics, and she was educated at a Catholic lyceum. By all accounts, she was brought up within the traditions and rites of the Catholic Church.

However, there is little to no evidence that Eva Braun was particularly devout or that her Catholic faith played a significant role in her adult life, especially after she entered Hitler’s orbit. Her life revolved around him, and her primary concerns were fashion, films, photography, and maintaining her position as his companion.

She lived a life of relative luxury and seclusion at the Berghof, Hitler’s mountain retreat, largely insulated from the political and ideological machinations of the Third Reich. It is highly unlikely that she would have challenged Hitler on matters of faith or philosophy. To do so would have been to challenge the very foundation of his worldview and her place within it.

Her presence does not suggest any softening of Hitler’s anti-Christian stance. His private circle was expected to conform, at least outwardly, to his way of thinking. The ultimate expression of their relationship and its disconnect from traditional religion came in their final hours. On April 29, 1945, in the Führerbunker beneath Berlin, Hitler and Eva Braun were married. The ceremony was a purely civil one, officiated by a minor city council official, Walter Wagner, who had been hastily brought in for the purpose.

There was no priest, no religious rite, and no mention of God. It was a stark, secular act designed to legitimize their union in the eyes of the state and “posterity” just before their joint suicide. This final act underscores the complete absence of traditional faith in their shared life. Eva Braun’s nominal Catholicism was a relic of her past, entirely subsumed by the all-encompassing and destructive reality of Hitler’s religion.

Hitler’s Comments in interviews about spirituality and Religion

Analyzing Adolf Hitler’s public and private statements on religion reveals a calculated and deeply cynical duality. He was a master of deception, tailoring his message to his audience. Publicly, he presented himself as a man of faith to win the support of the deeply Christian German populace. Privately, among his inner circle, he revealed his profound and venomous contempt for Christianity and outlined his vision for a new Nazi ideology to replace it.

In his early speeches and in Mein Kampf, Hitler frequently invoked the language of Christianity. He spoke of “the Lord,” “the Almighty,” and “Providence.” He famously wrote in Mein Kampf, “Hence today I believe that I am acting in accordance with the will of the Almighty Creator: by defending myself against the Jew, I am fighting for the work of the Lord.”

This was a strategic masterstroke. It framed his virulent antisemitism not as base racial hatred, but as a holy mission, co-opting religious language to sanctify his political goals. He negotiated the Reichskonkordat with the Vatican in 1933, a treaty that guaranteed the rights of the Catholic Church in Germany. He did this not out of respect for the Church, but to neutralize a potential source of opposition and gain international legitimacy.

To the German people, he presented Nazism and Christianity as compatible, even creating a state-sanctioned “Positive Christianity” movement, which sought to strip the faith of its Jewish origins and “un-German” teachings like compassion and forgiveness, and remold it into a faith that celebrated racial purity and militarism.

However, the private Hitler, as documented in sources like his Table Talk (transcripts of his dinner conversations) and the memoirs of his associates, held a completely different view. These sources, which Richard Weikart’s work draws upon, are crucial to understanding the true nature of Hitler’s religion. In private, he was scathing. He referred to Christianity as a “symptom of decay,” a “Jewish invention,” and a “religion for weaklings.” He stated, “The heaviest blow that ever struck humanity was the coming of Christianity.”

He lamented that Germany had adopted this “meek and flabby” faith instead of a more “manly, heroic” religion like that of the ancient Romans or the “warrior” faith of Islam, which he occasionally praised for its martial qualities. His plan was clear: during the war, he needed the churches for social cohesion, but after the “Final Victory,” he intended to completely crush them. He told his confidants, “The war will be over. The final battle will be for… the destruction of the Christ-idol… The dogma of Christianity gets worn away before the advances of science… In the long run, National Socialism and religion will no longer be able to exist together.” These private diatribes reveal the truth: his public piety was a mask, and his true faith was the brutal pseudo-religion of National Socialism itself.

Comparisons with other Dictators on Religion

To fully grasp the unique and central role of Hitler’s religion in his regime, it is illuminating to compare his approach to faith with that of other 20th-century dictators, particularly Joseph Stalin and Benito Mussolini. While all three sought absolute power and used ideology to control their populations, their relationships with organized religion differed significantly, highlighting the distinct nature of Hitler’s belief system.

Joseph Stalin, the ruler of the Soviet Union, was an avowed and militant atheist, a product of his Marxist-Leninist ideology. For Stalin, religion was, as Karl Marx had famously stated, “the opium of the people”—a tool of the ruling class to keep the proletariat docile and a direct competitor to the totalizing worldview of Communism. Consequently, the Soviet state under Stalin pursued a policy of brutal, systematic suppression of religion. The Russian Orthodox Church was viciously persecuted, with churches destroyed, property confiscated, and thousands of priests and believers executed or sent to the Gulag.

Stalin sought to completely eradicate faith and replace it with a state-enforced atheism and the cult of personality around himself and Lenin. His approach was one of direct annihilation. Hitler, by contrast, was more insidious. While he planned for the eventual destruction of Christianity, his own ideology was not atheistic. Hitler’s religion was a replacement faith, a pseudo-religion that mimicked the structure and fervor of traditional belief. He didn’t just want to create a spiritual vacuum; he wanted to fill it with his own doctrine of race and struggle, making his ideology a form of spiritual belief in itself.

Benito Mussolini in Fascist Italy presents another contrast. Unlike Stalin’s atheism or Hitler’s pseudo-religious fanaticism, Mussolini’s approach to religion was largely one of cynical pragmatism. Though an atheist in his youth, Mussolini recognized the immense power and influence of the Catholic Church in Italy. He understood that he could not rule effectively without coming to an accommodation with the Vatican. This led to the Lateran Treaty of 1929, which recognized Vatican City as an independent state and established Catholicism as the state religion of Italy.

For Mussolini, this was a political calculation, a way to win the support of Italian Catholics and bolster his regime’s legitimacy. He used the Church as a tool of statecraft. Hitler, on the other hand, saw his own worldview as a genuine spiritual truth. The Reichskonkordat he signed with the Vatican was, for him, a temporary tactical maneuver, not a lasting partnership. For Mussolini, religion was a useful instrument; for Hitler, his own ideology was the religion. This distinction is crucial: the horrors of the Third Reich were not just the result of political ambition but were driven by a deeply held, fanatical belief system that functioned as a religion, with its own ethics, cosmology, and soteriology (salvation through racial purity).

Religion’s Influence on Hitler’s Life

The influence of Hitler’s religion on his life and actions cannot be overstated; it was the central, animating force behind his political career and the atrocities of the Third Reich. His unique and toxic belief system was not a peripheral aspect of his personality but the very lens through which he viewed the world and the ideological engine that powered his destructive agenda. It provided him with a sense of ultimate purpose, a moral justification for unimaginable cruelty, and a blueprint for the society he sought to create.

First and foremost, his pseudo-religion provided the philosophical justification for war and genocide. By defining history as a racial struggle ordained by “Providence,” he elevated his political and military goals to the level of a holy crusade. The invasion of other countries was not mere conquest; it was the necessary acquisition of “Lebensraum” (living space) for the superior Aryan race to fulfill its destiny.

The Holocaust was not mass murder; it was a “sacred duty,” a cleansing act of “racial hygiene” to eliminate the “Jewish parasite” that he believed was poisoning humanity. As the provided context states, it is horrific that his “pseudo-scientific ideas led him to embrace a pseudo-religion that resulted in the deaths of millions.” This belief system allowed him and his followers to commit these acts not with a guilty conscience, but with a sense of righteous conviction. They were not breaking God’s laws; they were enforcing the higher laws of nature and blood.

Furthermore, this belief system fueled his powerful messianic complex. Hitler saw himself as more than just a politician; he viewed himself as a figure chosen by “Providence” to save the German people. He believed he was an instrument of a higher will, destined to lead Germany out of the humiliation of the Treaty of Versailles and into a glorious thousand-year Reich.

This conviction gave him an unshakable self-confidence and a charismatic power that mesmerized millions. His followers, in turn, did not just support a political leader; they revered a prophet and savior. This cult of personality was a core feature of the political religion of Nazism, demanding absolute faith and obedience.

Finally, Hitler’s religion shaped the very structure and rituals of the Nazi state. The Nuremberg Rallies were not political conventions; they were quasi-religious ceremonies with banners, processions, and “cathedrals of light,” all designed to create a sense of transcendent awe and collective identity. The SS, led by the occult-fascinated Heinrich Himmler, was envisioned as a new racial priesthood, with its own pagan-inspired rituals and strict codes of conduct based on “racial purity.” The entire state apparatus was geared towards propagating this new faith.

This demonstrates that Hitler’s religion was not just a private belief; it was a public, institutionalized ideology that sought to replace traditional morality and faith with a new, brutal creed based on race, struggle, and unwavering loyalty to the Führer.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the question of Hitler’s religion cannot be answered with a simple label. He was not an atheist, for he fervently believed in a guiding force he called “Providence.” He was certainly not a Christian, as he privately despised its core tenets of love and compassion, viewing it as a weak and corrupting influence he planned to eventually eradicate. Instead, Adolf Hitler was the high priest of his own dark and terrifying faith—a syncretic pseudo-religion built upon a foundation of misapplied social Darwinism, a pantheistic reverence for nature’s most brutal laws, and a messianic political ideology. This belief system provided the moral and spiritual justification for the unprecedented horrors of the Third Reich.

His worldview deified the Aryan race, demonized the Jewish people, and sanctified struggle and violence as the highest expressions of a divine natural order. As the provided context so powerfully concludes, “His example stands as a witness to the evil that can result from blinding oneself to the true God and his message of love and compassion for all.”

By transforming political ideology into a totalizing religious system, complete with its own sacred texts, rituals, and a messianic leader, Hitler unleashed a force of unparalleled destruction. Understanding the true nature of Hitler’s religion is essential, for it serves as a permanent and chilling reminder of how easily a worldview devoid of genuine compassion can lead humanity into its darkest abyss.

Related Queries

What was Positive Christianity?

Positive Christianity (Positives Christentum) was a movement within Nazi Germany that attempted to create a version of Christianity compatible with Nazi ideology. It sought to “Aryanize” the faith by rejecting the Old Testament and the Jewish origins of Jesus, denying his divinity, and recasting him as an Aryan warrior fighting against Jewish influence. It promoted the Nazi ideals of racial purity, nationalism, and obedience to the Führer, effectively stripping Christianity of its core doctrines of love, mercy, and universalism. While Hitler supported it tactically, his ultimate goal was the complete elimination of Christianity, not its reform.

Did Hitler believe in the occult?

This is a common point of fascination, but Hitler’s own beliefs were not primarily occultist. While some high-ranking Nazis, most notably SS leader Heinrich Himmler, were deeply invested in occultism, pagan rituals, and esoteric theories, Hitler was more pragmatic. His core beliefs were rooted in what he considered to be “science”—specifically, Social Darwinism and racial biology. He was often dismissive of Himmler’s more mystical pursuits. While the Nazi regime had occult elements, Hitler’s religion was more of a political and pseudo-scientific creed than a mystical one.

What did Hitler mean by “Providence”?

When Hitler used the term “Providence” (Vorsehung), he was not referring to the personal, loving God of Christianity. For him, Providence was an impersonal, deistic, or pantheistic force that operated through the unchangeable laws of nature. He believed this force had chosen him and the German people for a special destiny, and that history was guided by its iron law of racial struggle. It was a fatalistic concept that justified his actions as being in harmony with a higher, natural will, thus absolving him of personal moral responsibility.

Was Hitler an atheist?

No, Adolf Hitler was not an atheist. He frequently and fervently spoke of a creator, an “Almighty,” and “Providence.” Atheism, the belief in no god or divine force, was incompatible with his worldview. He needed a higher power to sanctify his mission and the laws of nature he claimed to be enforcing. However, his god was not the God of Abrahamic religions but a remote, impersonal force whose only law was the survival of the fittest. His belief system was a form of theistic ideology, not atheism.

How did Hitler view Islam?

Hitler held a complex and largely strategic view of Islam. In his private conversations, he sometimes expressed a grudging admiration for what he perceived as its “manly” and “warrior” characteristics, contrasting it favorably with the “meek” nature of Christianity. He believed its martial spirit would have been more suitable for the German people. This “admiration” was purely functional; he saw it as a more aggressive and world-conquering faith. During World War II, he also sought to use Islam as a political tool, attempting to incite Muslims in British- and French-controlled territories to rebel against the Allies.

FAQs About hitler religion

What religion was Hitler raised in?

Adolf Hitler was raised in a Roman Catholic family. His mother, Klara, was a devout Catholic, and he was baptized, confirmed, and even served as a choirboy in a monastery school during his youth. He later completely rejected his Catholic upbringing in favor of his own ideology.

Did Hitler try to destroy Christianity?

Yes, Hitler’s long-term goal was the complete eradication of Christianity in Germany. While he made temporary tactical alliances with the churches (like the 1933 Reichskonkordat), his private statements reveal a deep-seated hatred for the faith. He saw it as a rival ideology that promoted weakness and universalism, which was contrary to the Nazi focus on racial purity and struggle. His plan was to crush the churches after winning the war.

What is the main source for Hitler’s private religious views?

A primary source for his private views is the collection of conversations known as Hitler’s Table Talk, which were transcripts of his monologues delivered to his inner circle during the war. Additionally, the memoirs of his associates, such as Albert Speer and Joseph Goebbels, provide insight. Scholarly works, like Richard Weikart’s Hitler’s Religion, synthesize these sources to present a comprehensive picture of his beliefs.

Was Nazism considered a political religion?

Yes, many historians and sociologists classify Nazism as a “political religion.” This is because it exhibited many characteristics of a traditional faith: a messianic leader (Hitler), a sacred text (Mein Kampf), dogmatic beliefs (racial purity), elaborate rituals (Nuremberg Rallies), and a promise of salvation (a thousand-year Reich). It demanded total belief and sought to control all aspects of life, much like a totalitarian religious system.

Did Hitler believe he was chosen by God?

Hitler firmly believed he was chosen by a higher power, which he called “Providence,” for a special mission. He saw his survival of assassination attempts and his political successes as proof of this divine selection. This messianic complex was a central part of his psychology and a key element of his charismatic appeal, as he presented himself as a savior sent to redeem the German nation.

If you’re interested in learning more about religion, feel free to visit my website: whatreligionisinfo.com.